Synergizing Player and Character Skill

How to Make Both the Player and the Character Matter

Last week, we discussed how to manage the interface between the players and their characters. The core question of “what determines the outcome of player’s choices?” can be answered in four ways.

Character skill is paramount

Player skill is paramount

Character skill and player skill are non-overlapping magisteria

A synergy of both player and character skill

Having reviewed the first three options and found them wanting, we’ll now turn to the fourth option: synergizing player and character skill.

Example #1: The Player is the Instruction Booklet, the Character is the Guy Following the Instructions

Mitch is an expert in Krav Maga, where he learned how to disarm an intruder of a gun. His character Amdiron is a mage. Amdiron is currently being held at crossbow-point by an orc. Mitch says, “Amdiron knows its a mistake to menace someone at close range with a firear—I mean crossbow. Amdiron leans back against the crossbow subtly, then spins sideways and grabs the crossbow before the bolt can skewer him!” How does this get resolved?

I own a large number of US Army field manuals describing a number of useful skills, such as disarming explosives, building fortifications, zeroing a rifle, and more. I also own a number of field surgical guides with instructions on how to suture a wound, place a stint, and so on. I have many cookbooks with detailed recipes for creating crème brûlée and rolling sushi. I have accumulated a number of Ikea booklets with instructions on how to easily assemble a bookshelf or standing desk.

Despite having access to these instruction manuals, I am incompetent to perform any of these tasks. Whatever mechanical aptitude, muscle memory, motor steadiness, and other traits are required, I lack them. The bomb will certainly detonate if I disarm it. The rifle is zeroed in the sense that it hits zero targets when fired. The wound is so well sutured that you bleed to death. The bookshelf is crooked and collapses. The video “What REALLY happens when you build Ikea furniture” nicely illustrates this. (Watch it at 2x speed for true hilarity.)

In the synergistic approach, the player can instruct his character on what to do, but whether the character successfully does do it is up to the character. In Example #1, Amdiron’s attempt is resolved with an disarm special maneuver using Amdiron’s characteristics.

I started with this example because it’s the most straightforward to understand. It is also the most commonly utilized approach for combat in all tabletop RPGs.

Example #2. The Player Suspects, the Character Confirms

Example #2a. Ted is an avid RPG gamer. He has read every monster manual ever published. His character Athelstan is a 1st level cleric who has never left the temple before. Athelstan’s fellow adventurers are about to enter a moldy room. Ted says, “‘Wait! Athelstan warns everyone to stay back while he steps forward. Is this yellow mold?” How does this get resolved?

Example #2b. Luke has never played an RPG before. His character Süreus is a 1st level mage with INT 18 and Knowledge (molds and slimes) proficiency. Süreus’s fellow adventurers are about to enter a moldy room. Luke says, “‘Wait! Uh… does my guy know anything about the mold stuff? Is it safe to proceed?” How does this get resolved?

In ACKS, every character has the Adventuring proficiency. The Adventuring proficiency was a concept I developed to address exactly the situation described in Example #2a. Sometimes players know things. The Adventuring proficiency explains why they know the stuff players know — it represents the sort of broad-but-shallow know-how that gets picked up informally over time.

The Adventuring proficiency explains why Ted’s character Athelstan might know about yellow mold. He happened to hear a folktale about it once. Or his uncle Athelfred died to yellow mold. Ted is therefore perfectly within his rights to have Athelstan say “Wait! Is this yellow mold?”

What the Adventuring proficiency does not do is confirm whether the mold that looks yellow is actually Yellow Mold. To get confirmation, the character needs to have a proficiency such as Knowledge (molds and slimes), Loremastery, and so on.

In the synergistic approach to data about the world, the player suspects and the character confirms. To make this approach work, sometimes the player’s suspicions have to be wrong.

In Example #2a, the Judge might respond: “the mold has the color and texture of crème brûlée.” If Ted then asks, “does that mean it’s yellow mold, like, the monster that breathes death-spores?” the Judge would then respond “Athelstan doesn’t know. It might be, or it might just be mold that happens to be yellow.”

Or the Judge might respond “the mold has a reddish color, like congealed blood.” Ted, relieved it’s not yellow, says the party can advance. Sadly, the mold then explodes in a fireball. There’s no such monsters as “fire mold” in the ACKS rules, but the Judge has secretly created such a monster and placed it in his world. (Note how the Adventuring proficiency in the future would justify knowing about fire mold!)

In Example #2b, the Judge would respond “Süreus can make a Knowledge proficiency check.” If the proficiency check succeeds, the Judge might say “Based on his expert knowledge of molds, Süreus is certain this is harmless mold,” or “Süreus recognizes this as toxic mold,” or “Süreus knows this is a never-before-seen species of mold, closely related to yellow mold, but different.” If the proficiency check fails, the Judge simply says, “Süreus isn’t able to identify this species of mold.” He could share the info he shared with Ted, though, about its color and texture.

To my knowledge, ACKS is the only game that has an Adventuring proficiency that explicitly provides characters with the background knowledge that players bring into a game. But it’s easy to add to any game; and it makes resolving situations like these trivially easy.

Example #3. The Player Talks, the Character Translates

Example #3a. Chad is a highly successful business developer who teaches seminars on negotiation. His character, Rakh, is a berserker with a CHA of 7. Rakh is captured and brought before the king on charges of mayhem and vandalism. Chad says, “OK! Rakh bows deeply before the king and says the following: ‘Gracious majesty. If I have erred in my deeds in your kingdom, it is only because of a surfeit of martial vigor that lacks a proper outlet. Pray give me a quest worthy of my skill at arms and I will make right for you and your kingdom.” How does this get resolved?

Example #3b. Bob is a highly introverted theoretical botanist who hates human interaction. His character, Theodorus the Glorious, is a bard with a CHA of 18. Theodorus is captured and brought before the king on charges of cacophony and seduction of the innocent. Bob says, “Uh, Theodorus says whatever is appropriate to say to a king. Then he offers to hold a concert in the king’s honor but he makes it sound like a big deal.” How does this get resolved?

In the synergistic approach to interacting with NPCs, the player speaks and the character translates.

The king in Example #3 does not speak Modern English. He speaks Classical Auran (or Adûnaic or Aquilonian or whatever setting-specific tongue is involved). Chad and Bob do not speak any of those languages. They speak Modern English. How are Chad and Bob communicating with the king? Rakh and Theodorus are translating for them, from Modern English to Classical Auran.

Chad is a glib speaker of Modern English. Rakh, unfortunately, is a terrible translator. When Chad says “Gracious majesty. If I have erred in my deeds in your kingdom, it is only because of a surfeit of martial vigor that lacks a proper outlet. Pray give me a quest worthy of my skill at arms and I will make right for you and your kingdom,” Rakh says something like “gentle king, I broke your laws because I am strong and your kingdom is filled with weaklings. But maybe I could kill something for you since you can’t do it yourself?” Chad doesn’t know that’s what Rakh said, because he doesn’t speak Classical Auran. He just knows what he wanted Rakh to say. Sadly, Rakh’s plea probably doesn’t go too well. How badly it goes is resolved with a reaction roll using Rakh’s Charisma.

Conversely, Bob is a taciturn and hesitant speaker, but Theodorus is a fluent and diplomatic translator. When Bob says “say whatever is appropriate to say to a king,” Theodorus translates that beautifully into the diplomatically-appropriate wording. Again, Bob doesn’t know what Theodorus said, he just knows what he wanted him to say. Here, though, it probably goes well — how well is, again, resolved with a reaction roll using Theodorus’s Charisma.

Some people have a knee-jerk negative reaction to this approach. These players are usually excellent actors who make an effort to role-play their characters, and they feel it renders those efforts meaningless. It’s not fair, they’ll say, that Chad doesn’t get rewarded for his role-play. This is not an unreasonable criticism, but I don’t think its unanswerable. My answers are:

The player’s words are not rendered meaningless by the synergistic approach. The character is trying to follow his player’s intent to the best of his ability. “I would like to surrender” is never translated as “I am here to kill you.” “I will give you great wealth if you help me” is never translated as “I will give you sex if you help me.” In my games ACKS and Ascendant (both of which implement this approach), interaction is categorized as, e.g. Diplomacy, Intimidation, or Seduction, with different situational modifiers for each. Choosing which approach to take, and figuring out how to take advantage of the situational modifiers, is a matter of player skill. The player is the one “reading the room,” theorizing about the likely mindset of the NPCs, guessing what might entice them or frighten them.

The player’s tone and expression are not rendered meaningless either. The sentence “Why don’t we step outside to discuss the matter?” can convey a desire for intimacy with the subject, a lack of trust of others in the room, or a menacing threat, depending on tone and context. Chad, being skilled at role-play, can use tone and expression to bring his intent to life, and bring enjoyment to everyone at the table by doing so.

The character’s body language, body odor, appearance, and dress shouldn’t be rendered meaningless, but they often are if the player’s role-playing is given priority over the character. I can see “I’ll be back,” in an Austrian accent but no one is intimidated when I do because I’m not built like the Terminator.

So this approach is no way makes role-play unimportant. What it does do is give people like Bob a chance to enjoy playing someone they’re not in real life — a smooth and suave diplomat, a frightening menace, a sexy seducer, and so on.

Although not directly analogous, the video “The World’s Worst Translator” was inspirational to me in uncovering this principle. Check out for an incredibly funny example of mistranslation.

Example #4. The Player is the Boss, the Character Just Works Here; the Player Looks, but the Character Sees

Example #4. Jenna is a police detective. She is renowned for ability to spot the slightest disturbance in a crime scene. Her superhero RPG character, Dr. Disregard, is a mad scientist with her head in the clouds and the Unobservant drawback. Dr. Disregard is investigating a crime scene where a woman has been murdered. Jenna says, “Dr. Disregard begins to carefully investigate the crime scene. She subdivides it into one-meter square sections and then scan each one looking for anything out of the ordinary. I can go into more detail on each one meter by one meter area saying what she looks for if you want, but I’m talking dust, disturbances, hair, threads, fibers, blood spatter…” How does this get resolved?

The synergistic approach to investigation and searching is built on two facts. First, some people are conscientious and diligent about performing long detail-oriented tasks, and some people aren’t. Second, some people are mindful of details and some people are oblivious to them. In both cases, whether a long-detailed oriented task is completed successfully, or a minor detail is noticed, is essentially a stochastic output influenced by the person’s conscientiousness, diligence, and mindfulness

The easiest example I can offer is proofreading. Before I publish a rulebook, I send it to a proofreader for a thorough review. The proofreader reads the book cover to cover searching for errors. When the proofreader spots an error, I fix it. Nevertheless, errors creep in. If I tabulated every error in the book in advance, I would not be able to predict which errors would get spotted and which wouldn’t. It’s totally random. The proofreader's mind might wander on page 17 and miss an obvious “you’re” that should be a “your”. Doesn’t matter how hard the proofreader tries. Errors are unpredictable, undesired… yet, at scale, inevitable. I can’t predict the exact errors spotted, but I can reliably predict that if my best proofreader does the job, 95% of the errors will be spotted and 5% won’t. He succeeds on anything but a 1.

If a proofreader, diligently reading a rulebook line by line with bright lights, coffee, and a comfortable chair in an air-conditioned office, can’t reliably find all the errors, why do we expect that a thief working in a shadowy corridor with a clumsy pole will find all the traps? Just because a player wants his character to spend 10 minutes carefully plumbing every inch of the flagstones for cracks, that doesn’t mean the character actually manages to spend every second doing so without his mind wandering, and it doesn’t mean he actually finds all the cracks.

What is true for long and thorough searches is also true for instantaneous awareness. The mind is bombarded with sensation; it does not perceive all that it senses. If I misplace my keys on the kitchen table, they are effectively lost for all time, until my wife walks up and spends 0.5 seconds before noticing that they are in the fruit ball near the large banana with grey spots. How she is able to do this is an unfathomable mystery to me. I look, but she sees. No matter how much I look, I do not see.

The difference between the to do list, and the doing, between looking and seeing, between listening and hearing, needs to be modeled. In ACKS it’s modeled with things like proficiency throw to detect traps, while in Ascendant it’s modeled with an Observation or Investigation challenge action, and so on.

It is my judgment that this differential is where “rulings not rules” / “mother may I” gaming fails, because it assumes that characters are infallibly mindful and attentive as long as their players say they are. They aren’t. No one is. But some people are better at it than others, and so some characters are better at it than others.

An important corollary to the synergistic approach is that it means the gamemaster can and should modify the information he provides to the player based on the player’s character and rolls. In Example #4, Dr Disregard would make an Investigation check on the CHART, adding her Insight and Time spent to the Action Value (AV) and subtracting the Complexity of the crime scene as the Difficulty Value (DV). The result would reveal which Clues the gamemaster presents to Jenna. Depending on Dr. Disregard’s characteristics and roll, she might learn everything, something, or nothing from the effort.

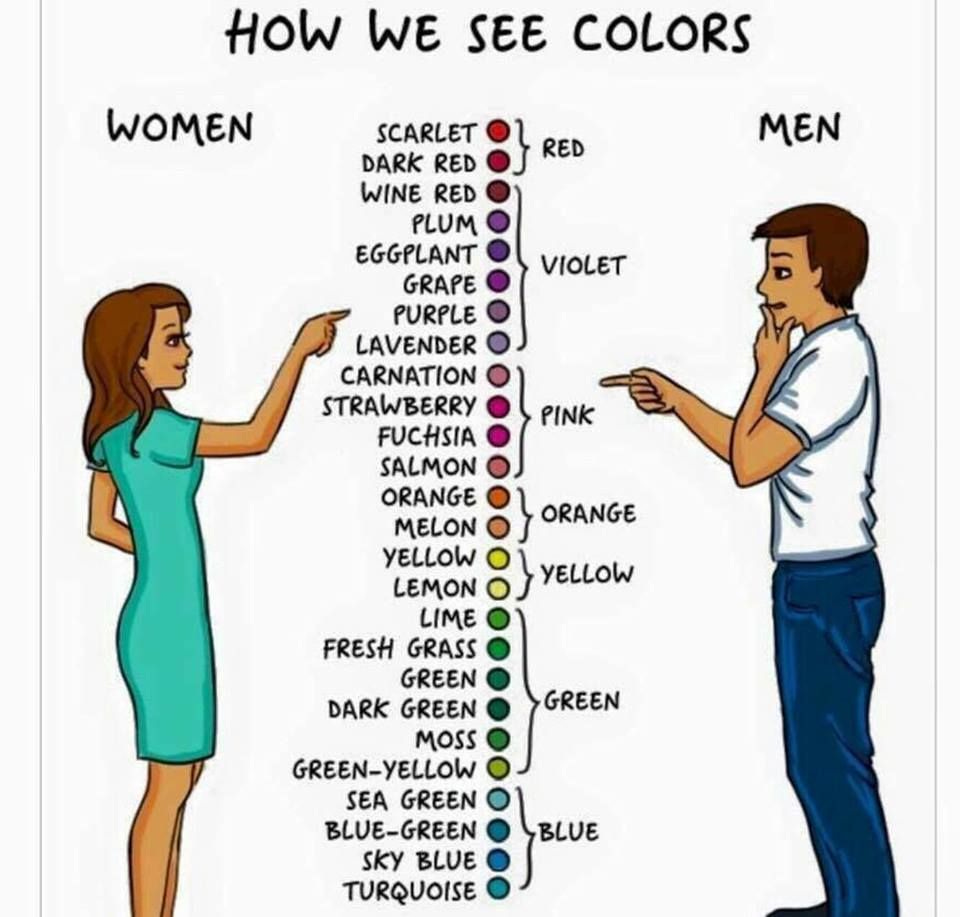

As this image humorously points out, “what color is the mold?” might actually be answered differently based on the character.

For a wonderful illustration of the ideas in this section, check out the video “If Women Had Hubby-Vision.” It’s a good laugh and illustrates the point well. (Lest someone misinterpret me, I don’t mean to imply that characters should have a modifier to perception checks by sex. It’s just those examples are easy to find in pop culture!)

Example #5. The Player is the Prefrontal Cortex, but the Character is the Amygdala

Example #5. Todd is a former special forces operator who earned a bronze star in war. His horror RPG character, Charlie Barker, is a nebbish accountant. Charlie finds himself hiding underneath a bed as an echolocating bat-thing prowls through the room looking for him. Todd says “Charlie stays utterly still. He doesn’t make a sound. He keeps his breathing light and shallow and his mouth shut.” How does this get resolved?

It’s often said that the player is the soul of the character. But which part of the soul? Since antiquity, sages have known that the soul or mind is fractured. Plato spoke of reason, spirit, and appetite as the three parts of the soul. 2500 years later, Freud spoke of supergo, ego, and id as the three parts of the mind. Contemporary neuroscientists speak of executive function being located in the prefrontal cortex, while emotional respond is modulated by the amygdala.

In the synergistic approach to player character behavior, the player’s skill represents the prefrontal cortex, while the character’s skill represents the amygdala. If you prefer, the player is the ego and the character is the id. We assume that most of the time, the player character is under the control of his reason, that his executive function is serving to bring about rational ends-oriented decision making. But sometimes the player character may succumb to his appetites, to his id, to the activation of his amygdala.

Here are some examples of such mechanics:

In Cyberpunk 2013, “your gun skills are really only how good you are on a nice, safe shooting range with no bullets zipping by. The picture changes drastically when actual shooting begins.” Characters are rated with a Combat Experience Modifier, that applies a penalty to their attack totals. “If your attack total is reduced to 0 or below, you are frozen with terror and unable to fight, only flee.”

In Mayfair’s CHILL, characters confronted by supernatural phenomenon must make Fear Checks. If they succeed, they can function normally. If they fail, they must flee or face penalties. Repeated exposure to particular monsters lets the character Resolve, which makes it possible to stay and fight.

In ACKS, a character confronted by a mummy must make a saving throw vs Paralysis or be paralyzed with terror until the mummy attacks or goes out of sight.

In Ascendant, a character can be subjected to Smack Talk. “Why don’t you leave those people alone and fight ME, tough guy!” If the Smack Talk succeeds, the character must either do what he was goaded into doing, or lose Determination (a type of mental hit points). Characters who lose all of their Determination become Overwhelmed and unable to function.

Mechanics like these do not necessarily detract from player agency. The body’s involuntary responses to stress are one of the challenges that the game world puts on characters, and it’s up to the players to figure out how to work with or around that fact.

Synergizing Player and Character Skill is the Optimal Approach for Tabletop RPGs

After 40 years spent playing tabletop RPGs and 11 years spent designing them, I’m convinced that synergizing player and character skill in the manner described above is the best choice for fun gameplay that maximizes player agency while still permitting players to play characters who are different than themselves.

All of my games have been built to take advantage of this approach. One of the surprises I encountered when I began interacting with my community more often (on Discord) was that many of them didn’t use it. Almost no one had understood how to use the Adventuring proficiency, or understood how I expected reaction rolls to be used with proficiencies, and so on. The fault is of course my own; I didn’t explain it well! This article has, hopefully, cleared that up, as well as gave some explanation as to why Ascendant is designed the way it is.

That doesn’t mean you have to play them that way. You can play ACKS with non-overlapping magisteria between player skill and combat skill, and lots of people do; if it works for them, I’m happy for them. Every campaign is a law unto itself.

Speaking Law… Please Enjoy this Short Primer on Dwarven Law

We’re less than a week away from the crowdfunding campaign for BY THIS AXE: The Cyclopedia of Dwarven Civilization. I’m pleased to report that the draft is complete, standing at a mighty 122,180 words and 192 pages. (Bonus goals will, doubtless, increase the size of the book.)

One of the sections I just finished is this summary of dwarven law. As a lawyer by training, I had fun with it.

The rules of law are written in stone – literally and figuratively. The throne room or great hall of every vault is engraved from floor to ceiling with the vault’s code of law. Once passed, a rule of law cannot be amended or overturned. It remains in effect perpetually thereafter, and is deemed to apply not just to the vault of the ruler who enacted it, but to all vaults that may later be founded by his subjects, or his subject’s descendants. Many of the laws of Azen Radokh were thus inherited from those of Azen Kairn, which in turn had inherited them from Azen Khador.

The irrevocable nature of dwarven law does not, however, impose as much of a burden on the dwarves as might be imagined. Dwarven rhetors are as ingenious as the best Auran jurists! Often the effects of a bad law can be circumscribed by later laws. For instance, one ancient law (dating to around 3,000 BE) I found in the archives stated that “only vaultguards have the right to carry arms to defend their vault.” Dating to a time when dwarves dwelled in isolation from other races, the law was probably intended to glorify the warrior class while limiting the clans from engaging in total war with each other. During the Bitter War, however, the dwarves found themselves in a total war – exactly what the law was intended to stop! Two new laws were passed, one stating that “all dwarves have the right to carry arms to defend their clan, guild, and family” and another that “every dwarf has a duty to defend his vault when given arms to do so by his lord.”

Although dwarven law is written in stone, it is still often the case that questions arise. How ought a law be interpreted? Has a particular action violated a law? What are the facts at hand, and who decides them? In the past, such matters were decided by force of arms. Armies of dwarves would assemble at an appointed time and place and battle each other until one side or the other yielded. The ancestors having rewarded the righteous with the blessings of victory, the matter was then considered justly resolved. In the Jutting Mountains, this practice is still used, but in the Meniri Mountains it is now considered to be needless bloodshed.

Instead, legal questions are decided in adversarial trials between the litigants. The litigants argue their case before a judge drawn from the ranks of the Highborn and a jury recruited by the litigants themselves. There is no limit to the size of a jury, so each side endeavors to get the most friends, guildmates, and family members to attend their jury summons. At the trial’s end, a majority vote of the jurors determines the outcome. In a sense, each side still raises an army to fight for their view, only now the issue is decided by a show of hands rather than a show of force. (Some of the leading Nicean cities use a similar jury, comprised of every citizen who shows up at an appointed place and time, to actually enact all of their laws!)

The litigants may speak on their own behalf, but usually choose to be represented by Craftborn dwarves from the College of Rhetors. These rhetors are highly trained in the argumentative arts and thoroughly schooled in the bewildering complexity of dwarven law. Successful rhetors are also exceptionally stalwart, because once begun a trial continues until both rhetors stop arguing. During this time, the rhetors are permitted neither to eat, drink, sit, sleep, or even relieve themselves. Only when both rhetors have finished presenting their arguments is the vote taken, and only those jurors who have endured the entire proceedings are permitted to vote. Some cases are left undecided because all the jurors abandon the trial before the rhetors finish talking. The rhetors often tacitly agree to stop talking if the jury seems on the verge of exhaustion, although if one side’s jurors are wavering and the others are not, the rhetors may push ahead. The most famous dwarven rhetor of all time, Larodin Tharkhad, won his most famous victory against the Terrace Farmer’s Guild by making his argument stretch all the way to harvest season. (Sadly it was his last victory, because he died moments thereafter when his bladder burst.)

I hope you will honor the sacrifice of Larodin Tharkhad and countless other dwarven rhetors by bringing an army to support the upcoming Kickstarter campaign. BY THIS AXE goes live on June 21st. Be there or shave your beard!

Join Me and Together We Can Rule the Mountains

Check out the links below for ways to get involved in the Autarch community. If you’re a fan, be kind and spread the word!

ACKS Patreon with a new article from our Axioms ezine every month

Ascendant Patreon with a new character and story hook every month

Autarch Facebook page with news and updates about our projects

Autarch Twitter channel with brief comments and witty quirks

Ascendant Comics Facebook page with sneak previews of the upcoming comics

Ascendant Comics Instagram page with tons of art and cosplay

Ascendant Comics Twitter channel with short messages and quirky wit